The Gustav Klimt Sale

Auction: 24/04/24

Exhibition: 13-21 April, 10am-5pm

Please note:

The Auction House reserves the right to request a deposit, bank guarantee or comparable other security in the amount of 10% of the upper estimate.

Purchase orders and accreditation requests must be received by the auction house up to 24 hours before the auction in order to guarantee complete processing.

Admission to the auction room is by appointment only and with a seat reservation. Registration at: gaber@imkinsky.com, +43 1 532 42 00 24

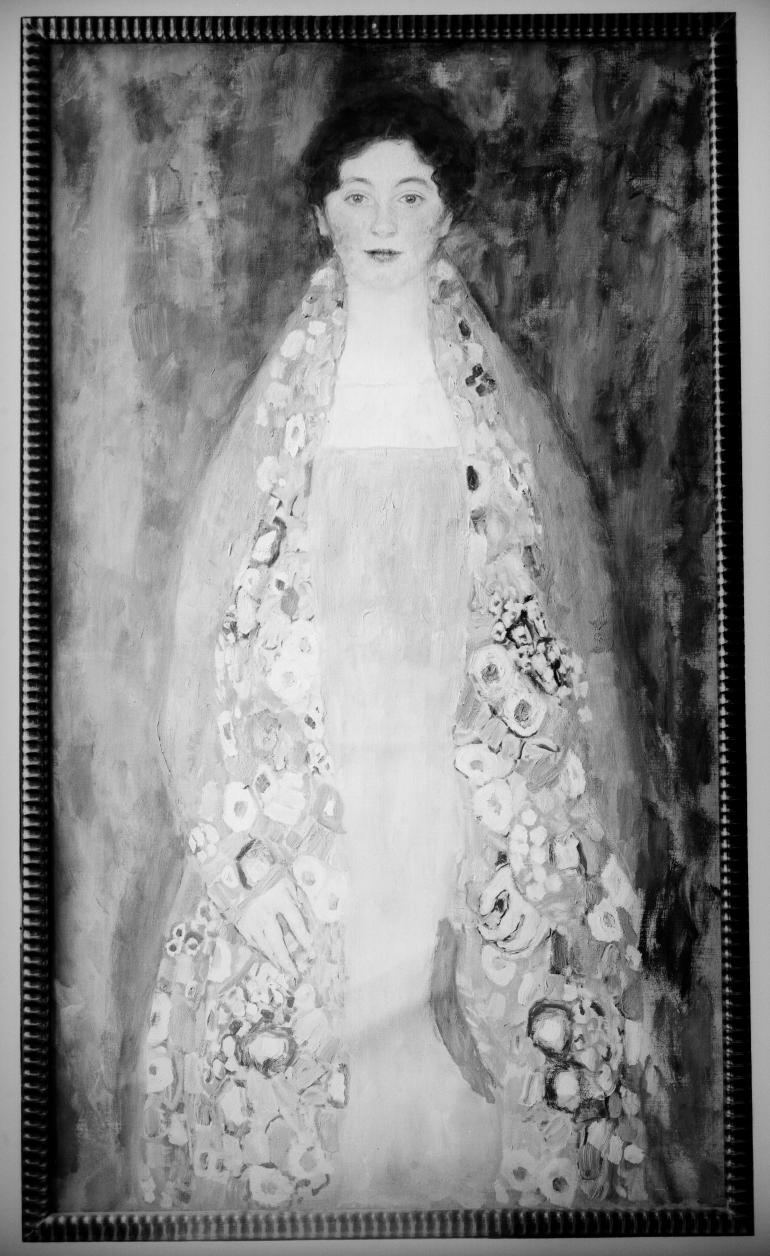

2 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Fräulein Lieser, b/w photo.

A portrait of a woman dating from Gustav Klimt’s late creative period, previously believed to be lost, stands as a major work in its own right. No matter where in the world and at which auction, the sale of such a painting is regarded as something special on the international art market. The fact that this rediscovered masterpiece of Austrian Modernism isn’t going to London or New York to be sold but is being auctioned in Vienna is a real sensation and sends out a clear signal to the German- speaking world.

The “Portrait of Fräulein Lieser” is one of Gustav Klimt’s last works. For many decades, it remained hidden in private Austrian ownership. The portrait is documented in the most important publications on Gustav Klimt’s oeuvre and was hitherto only known to experts from a black-and-white photograph (Fig. 2). (1) Thus up to now, it has only been possible to imagine the intense colours and painterly freedom of the painting, which make this one of the most beautiful portraits of Klimt’s final creative period.

3 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Fräulein Lieser, old frame (probably from 1925).

The background to the creation of the portrait

When Gustav Klimt immortalised “Fräulein Lieser” — as the sitter is called in the first catalogue raisonné published by Fritz Novotny and Johannes Dobai in 19672– she was a young lady of less than twenty. The notes in Klimt’s notebook from 1917 reveal further details of the circumstances surrounding the creation of the portrait: the sitter visited Klimt’s Vienna studio at Feldmühlgasse 11, Hietzing nine times in April and May 1917 to model for him. (3) This usually took place in the mornings, as Klimt’s notes on the times of the visits show. A list of his earnings in his sketchbook (Fig. 13) of the same year also shows that he received two payments on account of 5,000 Kronen each for the portrait on 18th May and 27th June. (4)

The family of the sitter belonged to the wealthy Viennese upper middle class, among whom Klimt found his patrons and clients. The brothers Adolf and Justus Lieser were two of the leading industrialists of the Austro- Hungarian monarchy. They had pioneered the jute and hemp industry in Austria. Thanks to the flourishing factory, “Lieser & Duschnitz, the first Austrian mechanical hemp mill, twine and rope factory” in Pöchlarn on the Danube, the family had become part of the wealthy business elite. (5) Henriette Amalie Lieser-Landau, known as “Lilly”, was married to Justus Lieser until 1905 and was the family’s best-known art sponsor. She frequented the artistic circles of the avant-garde, was a friend of Alma Mahler’s for many years, and supported the composers Arnold Schönberg and Alban Berg6 as a patroness of the arts.

4 Dancer Annie Lieser, 1923

Gustav Klimt’s reputation as a brilliant portraitist preceded him, which not only meant that he could command high prices for his paintings, but also made a portrait painted by him highly desirable to an educated, affluent public. There is much to suggest that it was the art-loving Lilly Lieser who commissioned Klimt to paint a portrait. (7) According to the latest provenance research, Klimt’s model was possibly not Margarethe Constance Lieser8, Lilly Lieser’s niece, but one of her two daughters: either Helene, the older one, born in 1898, or her sister Annie, who was three years younger. Helene Lieser was to make history in 1920, when she became the first woman in Austria to obtain a doctorate in Political Science. (9) Annie Lieser, who like her sister Helene attended Dr Eugenie Schwarzwald’s progressive “Reformschule”, was taught dance by Grete Wiesenthal and rose to become a celebrated expressive dancer (Fig. 4). (10)

On 11th January 1918, Gustav Klimt suffered a stroke from which he never recovered. He died on 6th February 1918 and the portrait of Fräulein Lieser was one of a considerable number of paintings that Klimt left behind in his studio. The painting subsequently went to the family who had commissioned it.

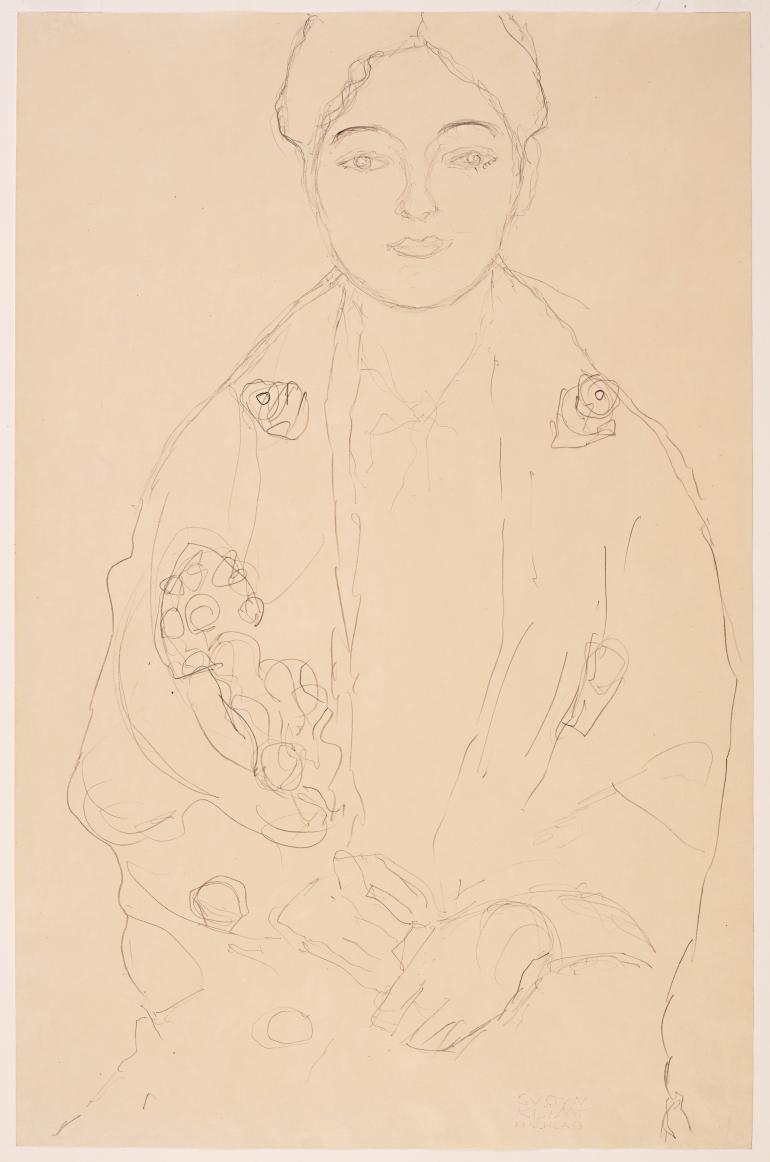

5 Gustav Klimt, Study for the Portrait of Fräulein Lieser, Seated Lady facing front with ornamented cape, 1917, Leopold Museum, Vienna.

The genesis of the painting: Preliminary studies

Commissioning a portrait from Klimt required not only financial backing but also patience, as Klimt was a perfectionist. He worked slowly, painting with tireless precision and preparing for his paintings with many studies. These drawings, which were an essential part of Klimt’s working process, show Klimt as a gifted graphic artist and - although they were mostly created in conjunction with paintings - have their own artistic value. There are 25 studies for the “Portrait of Fräulein Lieser”. (11) Quite a few of these drawings today form part of important museum and private collections, including the Leopold Museum in Vienna, the Wien Museum, the Lentos Linz and the Serge Sabarsky Collection in New York.

6 Gustav Klimt, Study for the Portrait of Fräulein Lieser, Seated to the left, knee-length portrait, 1917, private collection, New York

One study from the Leopold Museum collection is remarkably portrait-like in nature (Fig. 5). (12) It depicts the sitter en face and seated, with her hands clasped in her lap. The cloak already contains decorative designs, which have been replaced in the painting by a rich floral pattern.

In one drawing from an important private collection, Klimt varies the seated position by turning it slightly sideways, while the face remains turned towards the viewer (Fig. 6). (13) He studies the pretty facial features of his model and accentuates the expression of the eyes and the distinctive arch of the eyebrows. In this painting, it is the young woman’s alert, direct gaze that gives her a decidedly captivating presence. The wavy contour of the hair, which frames the face in a beautifully stylised way in the painted version, is also to be seen in this pencil drawing.

7 Gustav Klimt, Study for the Portrait of Fräulein Lieser, standing from the front, 1917, private collection, Austria.

In a larger series of studies, Klimt explored the frontal view and the standing pose that he opted for in the painting. A privately owned drawing, which was formerly part of the artist’s estate, shows the strictly frontal composition that becomes a defining feature of the painted portrait (Fig. 7). (14) The standing figure, over whose shoulders a shawl already reminiscent of the portrait has been draped, is cut off at the top and bottom by the edge of the paper and appears to be embedded in the surface of the picture due to its front-facing pose. Here, the oval shape of the face has been left without indicating any physiognomic features. With graphic sensitivity, Klimt uses sometimes delicate, sometimes bold lines to create a softly flowing outline, thus arriving at the wonderfully rhythmically curved contour of the sitter and her shawl in the painting.

9 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Mäda Primavesi, 1913, detail, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The painting

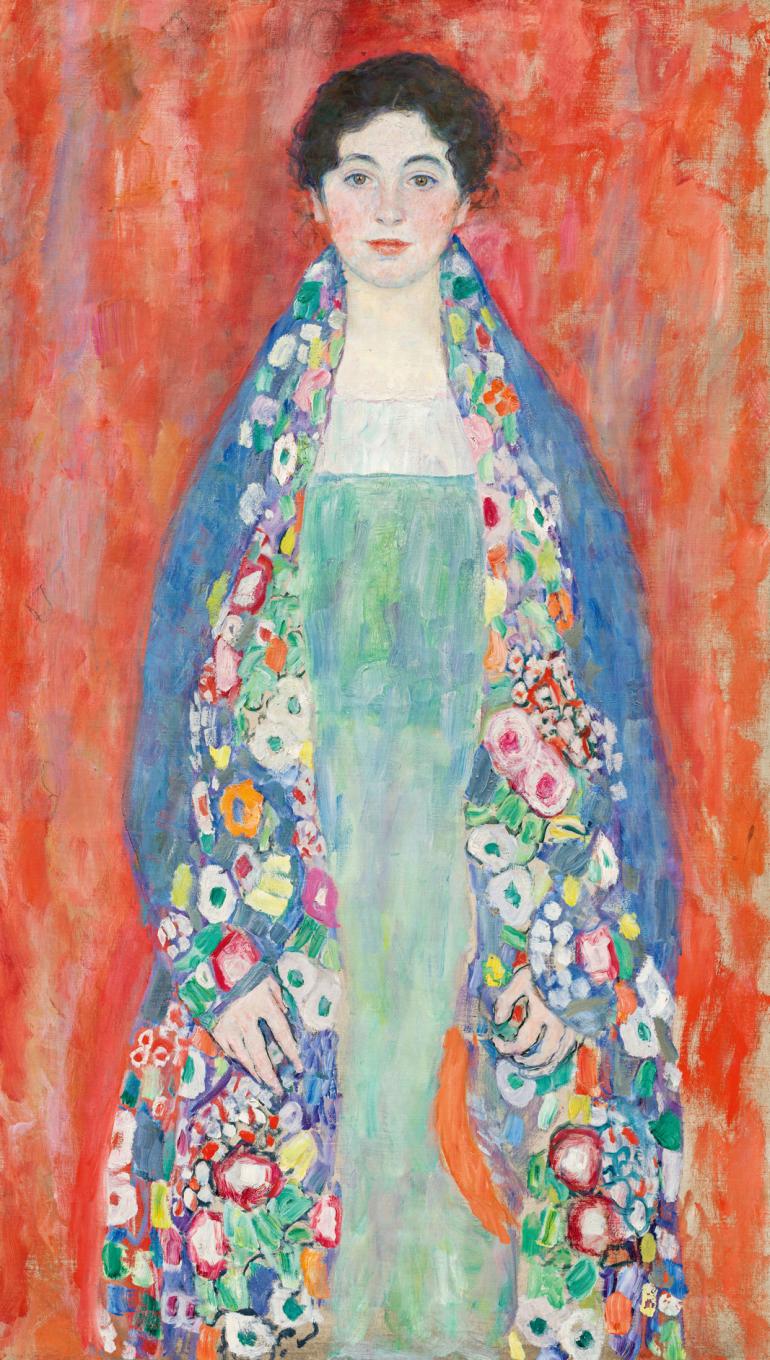

In the end, Klimt decides upon a three-quarter portrait in a strictly front-facing pose. The sitter is placed directly in the foreground of the scene, slightly removed from the upper edge of the picture and rising up like a stele — an artistic decision that makes her almost appear to hover. This impression is reinforced by the shimmering red of the background, which provides a fascinating insight into the painting process: here and there in the red area, Klimt has sketched in ornamentation which was never executed in paint (Fig. 8).

The skin tones have been painted with precise strokes, revealing the finest nuances of colour, for example, in the flushed cheeks or the blue shades in the area of the eyes and the hairline. By contrast, one is struck by the broad brushstrokes and the partly heavy impasto application of colour in the white blouse, the loosely falling green-turquoise dress and the shawl. In the background, the brushstrokes are longer, and have been applied in a dynamic and painterly, sometimes almost a crude, manner. Here, the painting achieves an astounding immediacy, with the red on the left being more thickly applied and the primed canvas still partly visible on the right. Klimt plays with complementary contrasts and colour resonances in a masterly way. As the defining element of the colour composition, the vivid red of the surroundings is echoed in Fräulein Lieser’s cheeks and sensually accentuated in her lips. The light green of the dress contrasts strikingly with the red tones.

Unlike Paul Cézanne, who worked on all the parts of a painting simultaneously in order to achieve balance and tension in its composition, Klimt initially focussed on the subtly nuanced treatment of the skin tones. Fräulein Lieser’s face and hands, outlined in black, are depicted in full detail. Her dress and the shawl with its floral design also display a high degree of completeness. In the floral pattern, the shapes are delineated more lavishly in some places and the open background forms part of the composition of the painting. The surroundings were left still largely undefined at the end of the work’s genesis.

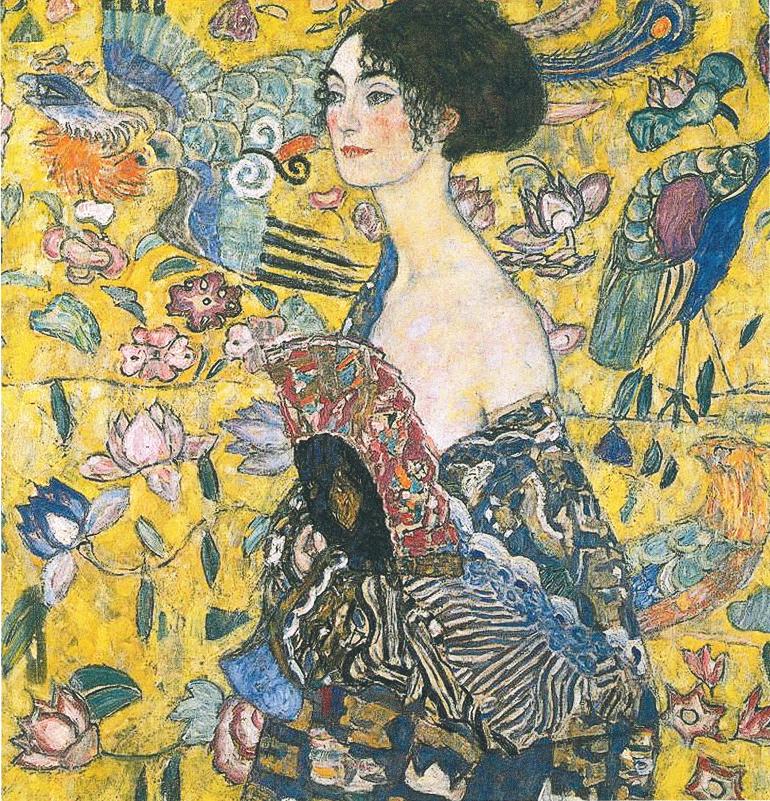

11 Gustav Klimt, Lady with a Fan, 1917, private collection.

The ornamental motifs drawn on the red of the background indicate the start of elaborating a decorative

design surrounding the figure. But how would Klimt have further developed these graphic outlines in painting? Other portraits of ladies from his late creative years show different design variations. One of the completed paintings is the “Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer”(15) (Fig. 20), which is similar to the Lieser portrait in its front-facing pose and sweeping symmetrical contours. In the upper half of the picture, Asian figures are grouped around Elisabeth Lederer, surrounding her at a fitting distance like an aureole. The “Portrait of Ria Munk III”16, which likewise remained unfinished due to the artist’s death, features a dense, colourful arrangement of flowers. The figure of Ria Munk is enveloped in an aura of flowers, intermingled with tendrils and motifs of a profoundly symbolic nature. (17) We are familiar with the exuberantly filled composition, reminiscent of a “horror vacui”, of the “Portrait of Friederike Maria Beer” (18) (Fig. 27), which was completed in 1916. Again, in the painting “Lady with a Fan” (19) (Fig. 11), we find a scatter pattern of symbols adapted from Asian art, strewn across a background of yellow wallpaper. Klimt’s own Asian artefacts, with which he surrounded himself in his studio in Hietzing, served as a source of inspiration for his repertoire of shapes and motifs. There was also a carpet there designed by Josef Hoffmann, with a diamond motif in its pattern that recurs in a strikingly similar form in the Lieser portrait: Klimt has sketched the diamond with inwardly curved sides as a decorative element in the red background. The scattered linear patterns sketched into the red in the Lieser portrait suggest that Klimt would have enriched the painting with ornamental touches but was by now only missing a few background details. A rather sparse backdrop is imaginable, possibly similar to the one we know from the vibrant pink-purple upper background of the portrait of nine-year-old Mäda Primavesi (Fig. 9), which is enlivened with stylized floral motifs.

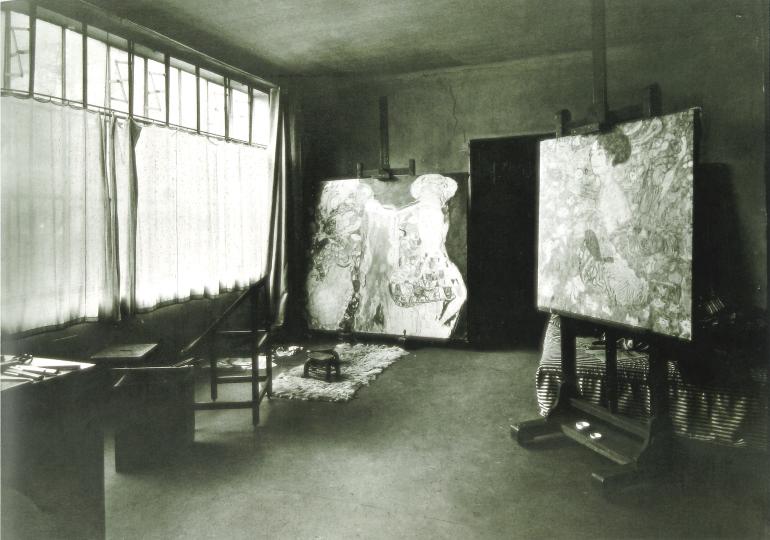

12 Klimt’s studio at Feldmühlgasse 11 shortly after the artist’s death, 1918

Gustav Klimt was a painter who pursued trailblazing developments and new means of artistic expression. From his Secessionist works at the beginning of Modernism to his icons of the Golden Period and his late work, he always drew on new influences to further develop his unique pictorial language. After abandoning the use of gold in his paintings, it was his encounter with the works of the Fauves and the Post-Impressionists that steered his work in a new direction in which colour took on a pictorial significance. The “Portrait of Fräulein Lieser” vividly illustrates the extent to which he embraced the power of colour and a new painterly freedom in his last paintings. The intensive colouring of the painting and the focus on light, open brushwork reveal Klimt at the height of his late creative period.

The painter’s death in February 1918 prevented the completion of the portrait. Klimt himself found it difficult to regard a painting as complete. Thus, he worked on his paintings for years, sometimes exhibiting them in an unfinished state and continuing to make changes to them later. The Lieser painting is one of those late works of Gustav Klimt whose special appeal is also partly due to the “finished or unfinished” question. While large parts of the painting can be regarded as finished, some details still await their final realisation in paint. The preliminary sketches in the red background suggest that Klimt would only have made very sparing additions to the picture. Yet is it not precisely the nature of the unfinished that is fascinating from today’s perspective, since it intensifies the painterly openness and expressiveness of this picture? There is no doubt that a work that is in some way “unfinished” particularly appeals to our curiosity, imagination and ability to find associations. What might Klimt have added to the painting next? Would he have offered us still more chromatic refinements? And would it have been possible for any of them to increase the breathtaking beauty of this painting, preserved in its original state?

Mag. Claudia Mörth-Gasser is an art historian and court-certified expert. She is head of the modern art department at the auction house im Kinsky.

1 Picture Archive of the Austrian National Library, Negative 113.741.

2 Novotny/Dobai 1967, No. 205, p. 367.

3 Cf. Krug, Gustav Klimt’s Last Notebook, in: Price 2007, pp. 220–221. We should like to thank Dr Hansjörg Krug for making his 2007 typescript “Gustav Klimt’s last notebook” available to us.

4 Strobl 1984, Vol. III, p. 242, Fig. c.

5 Cf. Gaugusch 2016, pp. 1899–1902.

6 Cf. Irene Suchy, “Lilly Lieser – Eine Übersehene, Eine Co-Produzentin der Schönberg’schen Musikgeschichte”, (“Lilly Lieser – An overlooked figure, a co-producer of Schönbergian music history”) in: Österreichische Musikzeitschrift 10, 2008, p. 6–16.

7 Cf. Ernst Ploil’s remarks on “Geschichte und Provenienz” (“History and Provenance”) in this catalogue.

8 Alice Strobl identified the sitter as “Margarethe Constance Lieser”, cf. Strobl 1984, Vol. III, p. 112. Weidinger (2007) and Natter (2012) followed Alice Strobl’s identification of the sitter in their catalogues raisonnés.

9 Cf. Gaugusch 2016, p.1901.

10 Cf. http://biografia.sabiado.at/becker-annie-edle-von/ (accessed on 11.12.2023).

11 Strobl 1984, Vol. III, No. 2584–2605, pp. 120–123. We should like to thank Dr Marian Bisanz-Prakken for the valuable information that, in addition to the 22 studies published in Alice Strobl’s catalogue raisonné in connection with the “Portrait of Fräulein Lieser”, she will be including three additional sheets in the supplementary volume on the catalogue raisonné of drawings..

12 Strobl 1984, Vol. III, No. 2603, Fig. p. 123.

13 Strobl 1984, Vol. III, No. 2605, Fig. p. 123.

14 Strobl 1984, Vol. III, No. 2587, Fig. p. 121.

15 Natter 2012, No. 212.

16 Natter 2012, No. 236.

17 On the symbolism of the painting “Ria Munk III” cf. the article by Marian Bisanz- Prakken, “Ria Munk III von Gustav Klimt. Ein posthumes Bildnis neu betrachtet” (“Ria Munk III by Gustav Klimt. A new look at a posthumous portrait”), in: Parnass, issue 3/2009, Sept./Oct., p. 54–59.

18 Natter 2012, No. 145.

19 Natter 2012, No. 237.