0019

Gustav Klimt

(Wien 1862 - 1918 Wien)

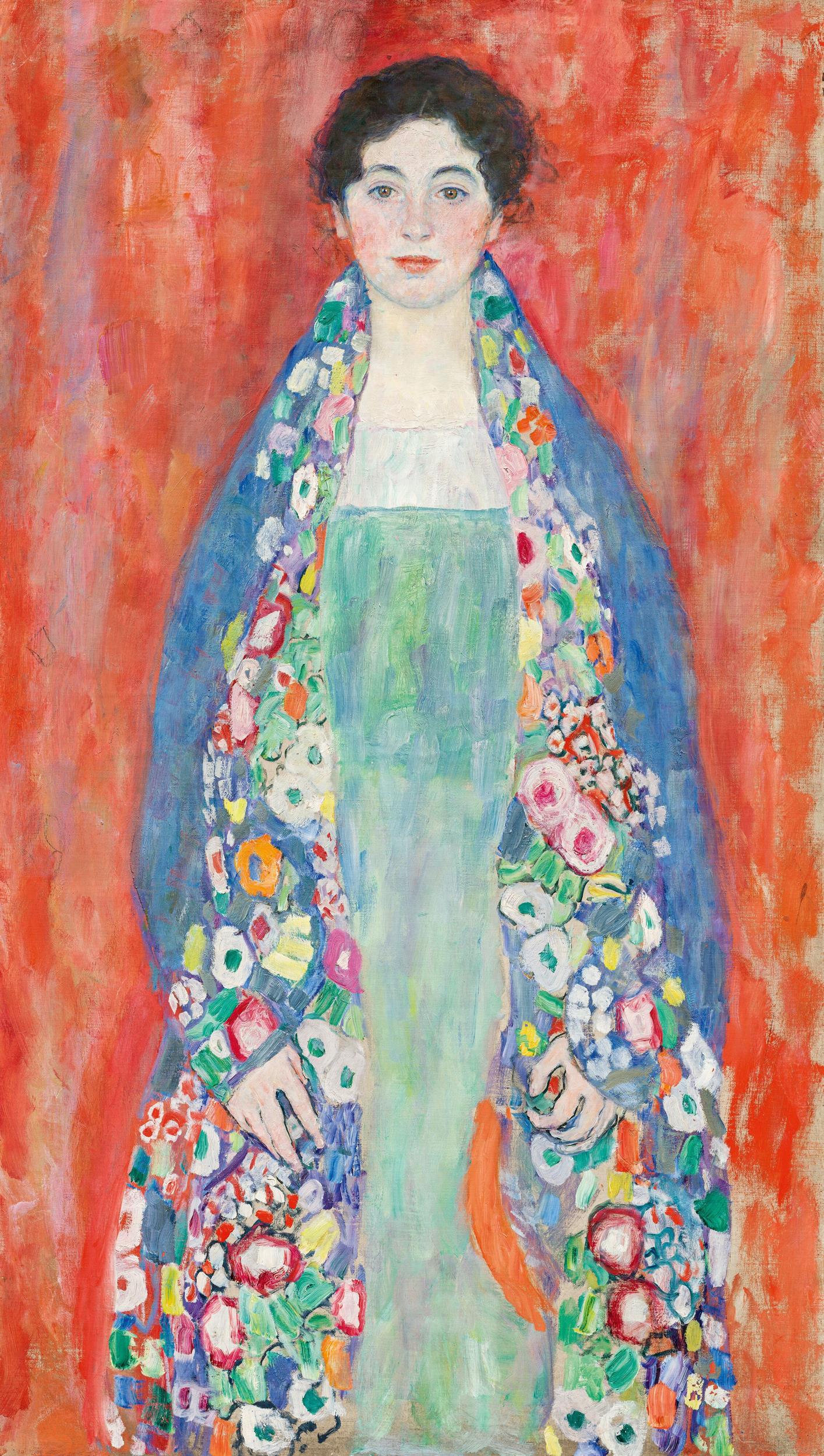

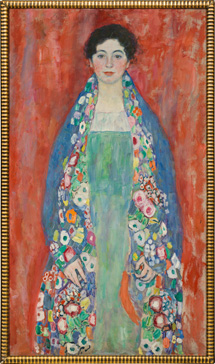

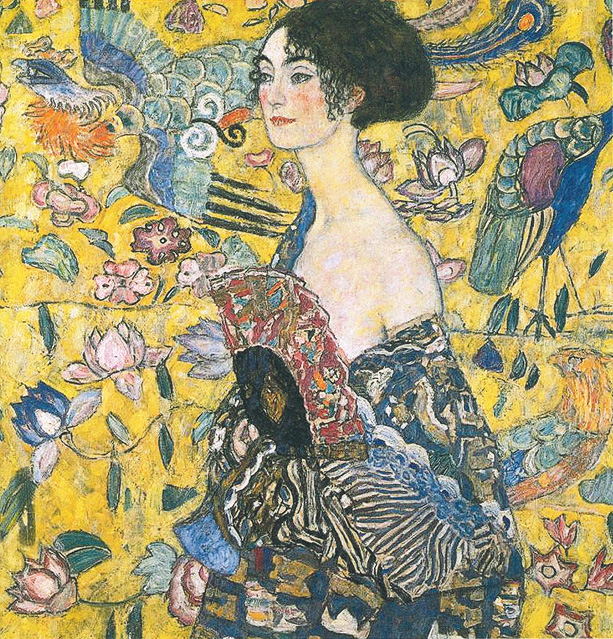

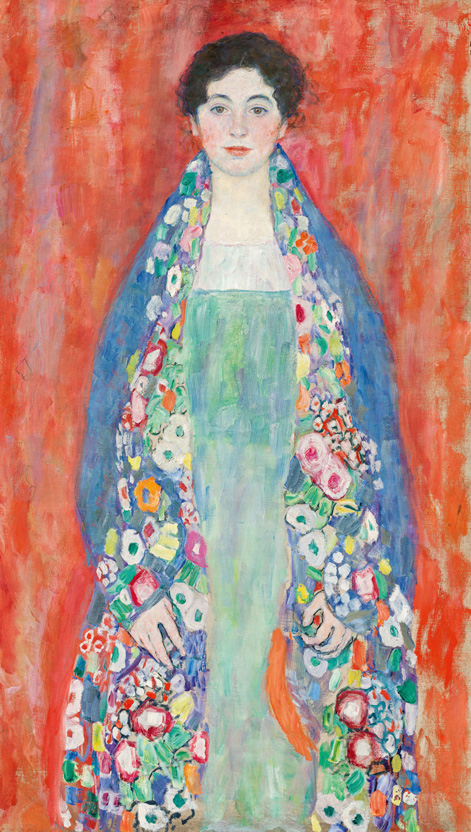

„Portrait of Fräulein Lieser“

1917

oil on canvas; framed

140 x 80 cm

The painting is in very good, original condition.

Detailed conservation report by Mag. Alexandra Grausam, Atelier Siebenstern Vienna, on request.

Certificate The Art Loss Register, London, 13 April 2023 was issued (ALS Ref: S00230833).

A legally binding permit from the Austrian Federal Monuments Authority (decision dated 23 October 2023) for the export of the painting was issued.

This artwork is being auctioned on behalf of the current owners (Austrian private property) and the legal successors of Adolf and Henriette Lieser based on an agreement in accordance with the Washington Principles.

Result: € 38.500.000 (incl. fees and Austrian VAT)

Auction is closed.

The Auction House reserves the right to request a deposit, bank guarantee or comparable other security in the amount of 10% of the upper estimate. Please also note that purchase orders and accreditation requests must be received by the auction house up to 24 hours before the auction in order to guarantee complete processing.

Provenance:

from the estate of the artist;

Henriette Lieser or Adolf Lieser, Vienna;

possibly art market, Vienna;

Austrian private property since the 1960s

Exhibition:

Vienna 1926, Neue Galerie, Otto Nirenstein, 23rd exhibition, Gustav Klimt, 20 May-late June. (cf. notes by Otto Kallir-Nirenstein, Archive Neue Galerie, no. 384/7). The painting was to be included in the Klimt exhibition of Otto Kallir-Nirenstein, but it was probably not exhibited there.

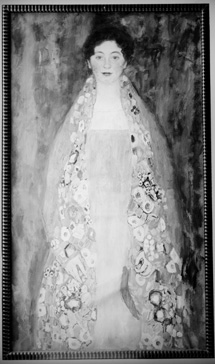

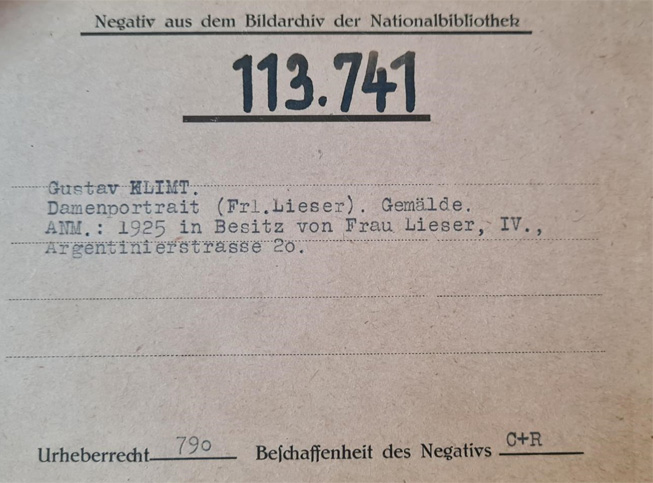

The black-and-white photograph, negative 113.741, from the picture archive of the Austrian National Library (with the note: „Gustav Klimt. / Damenportrait (Frl. Lieser). Gemälde. / ANM.: 1925 in Besitz von Frau Lieser, IV., / Argentinierstrasse 20.") is probably related to this Klimt exhibition, which was originally scheduled to open on 10 October 1925 in the rooms of the Hagenbund.

Literature:

Johannes Dobai, Das Frühwerk Gustav Klimts, thesis, Vienna 1958, no. 191, p. 169 (without ill.);

Fritz Novotny/Johannes Dobai, Gustav Klimt. Katalog der Gemälde, Salzburg 1967, 1st edition, no. 205, p. 367, pl. 103, b/w-ill.;

Alice Strobl, Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen 1912-1918, vol. III, Salzburg 1984, p. 111f., b/w-ill. p. 114 and studies nos. 2584-2605, p. 120-124;

Alfred Weidinger (ed.), Gustav Klimt. Kommentiertes Gesamtverzeichnis des malerischen Werkes von Alfred Weidinger, Michaela Seiser, Eva Winkler, Munich et al. 2007, no. 245, b/w-ill. p. 306;

Dr. Hansjörg Krug, „Gustav Klimt‘s Last Notebook“, in: Renée Price (ed.), The Ronald S. Lauder and Serge Sabarsky Collections, catalogue Neue Galerie New York, Munich et al. 2007, p. 220f.;

Tobias G. Natter (ed.), Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Cologne 2012, no. 235, b/w-ill. p. 637;

Georg Gaugusch, Wer einmal war. Das jüdische Großbürgertum Wiens 1800-1938. L-R, Vienna 2016, p. 1899-1902;

Gustav Klimt-Database, Klimt-Foundation, Vienna: https://www.klimt-database.com/de/klimt-werk/1914-1918/maler-der-frauen/ (accessed on 07.12.2023; „Unvollendete Aufträge und verschollene Porträts", without ill.);

Olga Kronsteiner, Die lange Reise des „Fräulein Lieser“, in: Der Standard, 20.02.2024, p. 19

- The “Portrait of Fräulein Lieser” by Gustav Klimt

- History and Provenance

- From black and white to colour

- Less is More

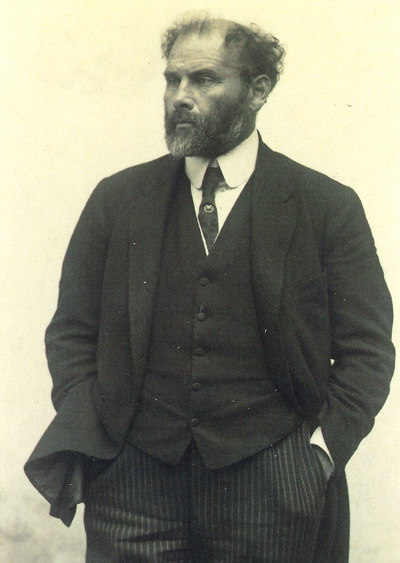

- Gustav Klimt

- Sources of figures

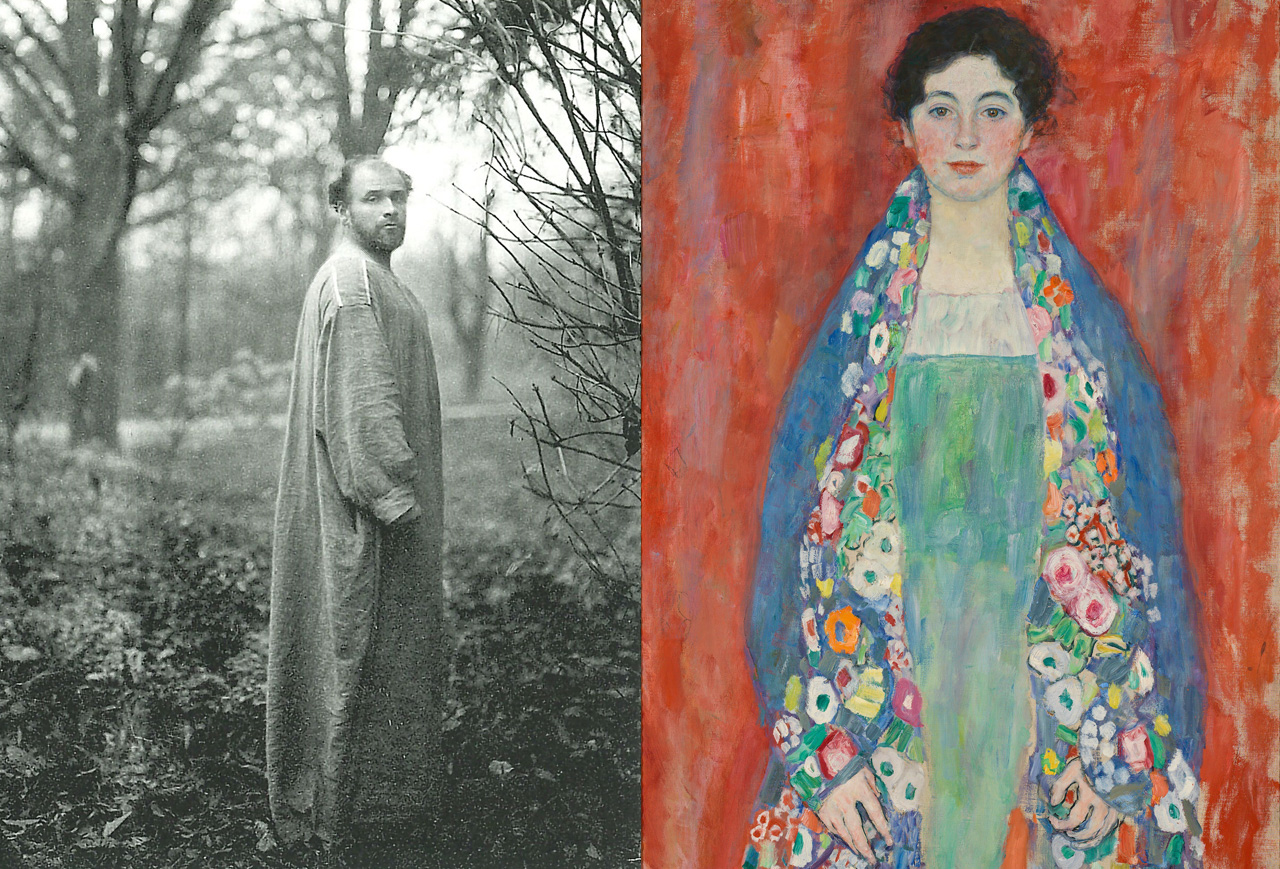

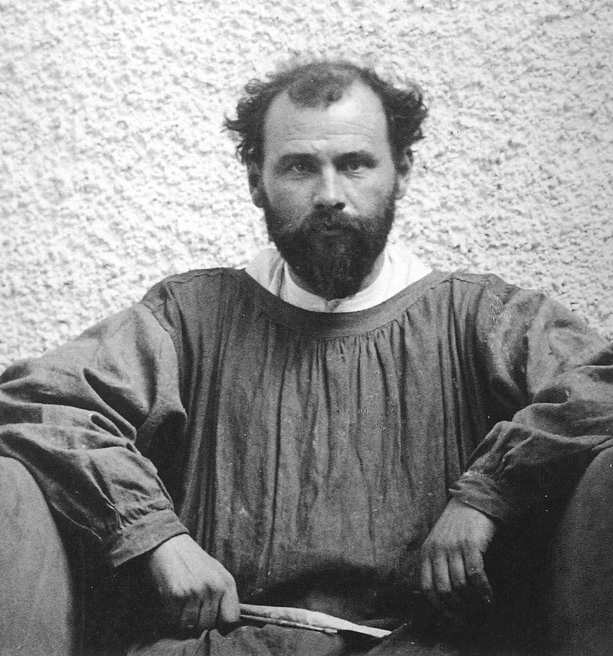

1 Gustav Klimt in the garden in front of his studio at Josefstädter Straße 21, around 1909

The “Portrait of Fräulein Lieser” by Gustav Klimt

A great rediscovery

Claudia Mörth-Gasser

A portrait of a woman dating from Gustav Klimt’s late creative period, previously believed to be lost, stands as a major work in its own right. No matter where in the world and at which auction, the sale of such a painting is regarded as something special on the international art market. The fact that this rediscovered masterpiece of Austrian Modernism isn’t going to London or New York to be sold but is being auctioned in Vienna is a real sensation and sends out a clear signal to the German-speaking world. The “Portrait of Fräulein Lieser” is one of Gustav Klimt’s last works. For many decades, it remained hidden in private Austrian ownership. The portrait is documented in the most important publications on Gustav Klimt’s oeuvre and was hitherto only known to experts from a black-and-white photograph (Fig. 2).1 Thus up to now, it has only been possible to imagine the intense colours and painterly freedom of the painting, which make this one of the most beautiful portraits of Klimt’s final creative period.

2 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Fräulein Lieser, b/w photo

3 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Fräulein Lieser, old frame (probably from 1925)

The background to the creation of the portrait

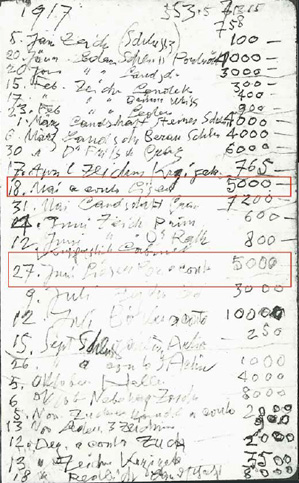

When Gustav Klimt immortalised “Fräulein Lieser” — as the sitter is called in the first catalogue raisonné published by Fritz Novotny and Johannes Dobai in 19672 – she was a young lady of less than twenty. The notes in Klimt’s notebook from 1917 reveal further details of the circumstances surrounding the creation of the portrait: the sitter visited Klimt’s Vienna studio at Feldmühlgasse 11, Hietzing nine times in April and May 1917 to model for him.3 This usually took place in the mornings, as Klimt’s notes on the times of the visits show. A list of his earnings in his sketchbook (Fig. 13) of the same year also shows that he received two payments on account of 5,000 Kronen each for the portrait on 18th May and 27th June.4 The family of the sitter belonged to the wealthy Viennese upper middle class, among whom Klimt found his patrons and clients. The brothers Adolf and Justus Lieser were two of the leading industrialists of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy.

They had pioneered the jute and hemp industry in Austria. Thanks to the flourishing factory, “Lieser & Duschnitz, the first Austrian mechanical hemp mill, twine and rope factory” in Pöchlarn on the Danube, the family had become part of the wealthy business elite.5 Henriette Amalie Lieser-Landau, known as “Lilly”, was married to Justus Lieser until 1905 and was the family’s best-known art sponsor. She frequented the artistic circles of the avant-garde, was a friend of Alma Mahler’s for many years, and supported the composers Arnold Schönberg and Alban Berg6 as a patroness of the arts.

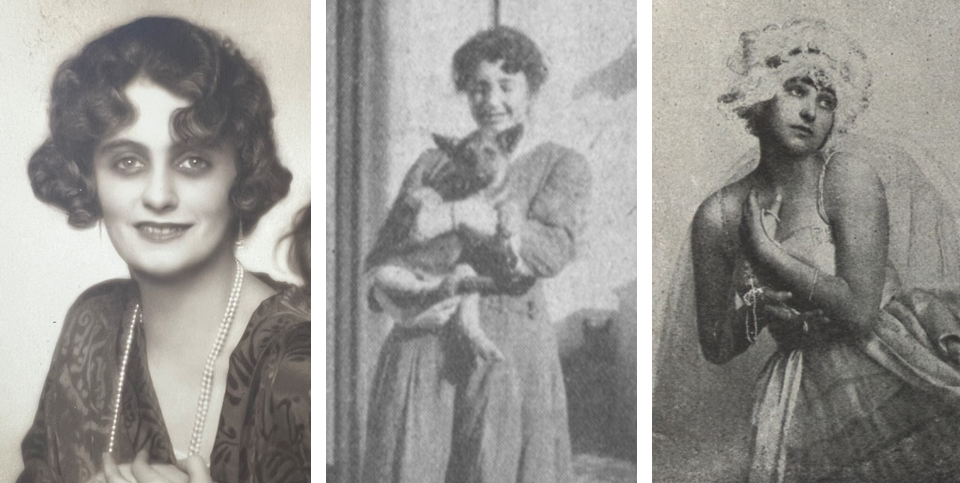

Gustav Klimt’s reputation as a brilliant portraitist preceded him, which not only meant that he could command high prices for his paintings, but also made a portrait painted by him highly desirable to an educated, affluent public. There are suggestions that it was the art-loving Lilly Lieser who commissioned Klimt to paint a portrait.7 According to the latest provenance research, Klimt’s model was possibly not Margarethe Constance Lieser8, Lilly Lieser’s niece, but one of her two daughters either Helene, the older one, born in 1898, or her sister Annie, who was three years younger (Fig. 4).9

On 11th January 1918, Gustav Klimt suffered a stroke from which he never recovered. He died on 6th February 1918 and the portrait of Fräulein Lieser was one of a considerable number of paintings that Klimt left behind in his studio. The painting subsequently went to the family who had commissioned it.

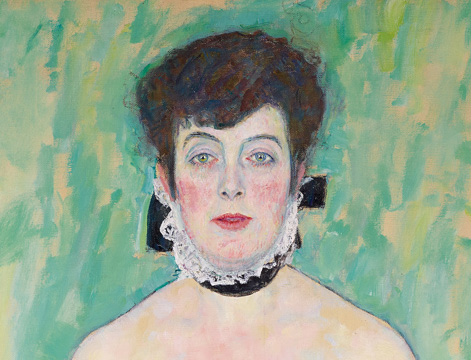

4 Margarethe Constance Lieser, Helene Lieser, Annie Lieser.

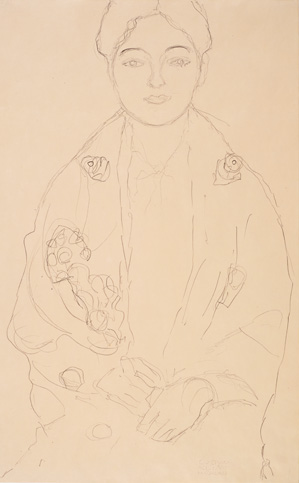

The genesis of the painting: Preliminary studies

Commissioning a portrait from Klimt required not only financial backing but also patience, as Klimt was a perfectionist. He worked slowly, painting with tireless precision and preparing for his paintings with many studies. These drawings, which were an essential part of Klimt’s working process, show Klimt as a gifted graphic artist and - although they were mostly created in conjunction with paintings - have their own artistic value. There are at least 25 studies for the “Portrait of Fräulein Lieser”.10 Quite a few of these drawings today form part of important museum and private collections, including the Leopold Museum in Vienna, the Wien Museum, the Lentos Linz and the Serge Sabarsky Collection in New York.

One study from the Leopold Museum collection is remarkably portrait-like in nature (Fig. 5).11 It depicts the sitter en face and seated, with her hands clasped in her lap. The cloak already contains decorative designs, which have been replaced in the painting by a rich floral pattern. In one drawing from an important private collection, Klimt varies the seated position by turning it slightly sideways, while the face remains turned towards the viewer (Fig. 6).12 He studies the pretty facial features of his model and accentuates the expression of the eyes and the distinctive arch of the eyebrows. In this painting, it is the young woman’s alert, direct gaze that gives her a decidedly captivating presence. The wavy contour of the hair, which frames the face in a beautifully stylised way in the painted version, is also to be seen in this pencil drawing.

5 Gustav Klimt, Study for the Portrait of Fräulein Lieser, Seated Lady facing front with ornamented cape, 1917, Leopold Museum, Vienna

6 Gustav Klimt, Study for the Portrait of Fräulein Lieser, Seated to the left, knee-length portrait, 1917, private collection, New York

7(Kat.-Nr. 18) Gustav Klimt, Study for the Portrait of Fräulein Lieser, standing from the front, 1917, private collection, Austria

In a larger series of studies, Klimt explored the frontal view and the standing pose that he opted for in the painting. A privately owned drawing, which was formerly part of the artist’s estate, shows the strictly frontal composition that becomes a defining feature of the painted portrait (Fig. 7).13 The standing figure, over whose shoulders a shawl already reminiscent of the portrait has been draped, is cut off at the top and bottom by the edge of the paper and appears to be embedded in the surface of the picture due to its front-facing pose. Here, the oval shape of the face has been left without indicating any physiognomic features. With graphic sensitivity, Klimt uses sometimes delicate, sometimes bold lines to create a softly flowing outline, thus arriving at the wonderfully rhythmically curved contour of the sitter and her shawl in the painting.

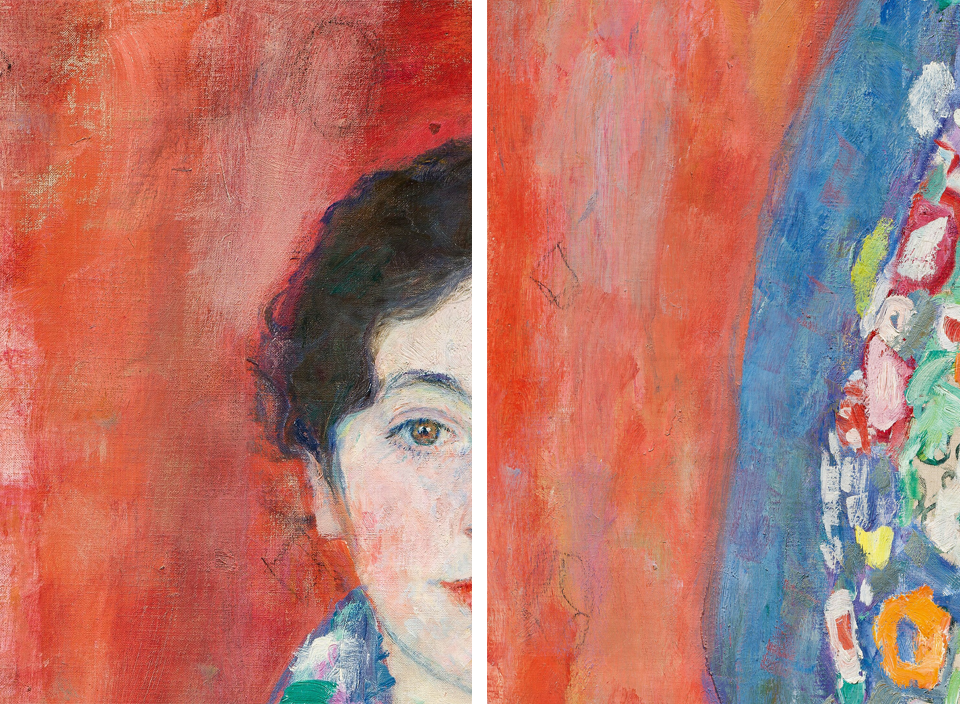

The painting

In the end, Klimt decides upon a three-quarter portrait in a strictly front-facing pose. The sitter is placed directly in the foreground of the scene, slightly removed from the upper edge of the picture and rising up like a stele — an artistic decision that makes her almost appear to hover. This impression is reinforced by the shimmering red of the background, which provides a fascinating insight into the painting process: here and there in the red area, Klimt has sketched in ornamentation which was never executed in paint (Fig. 8).

8 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Fräulein Lieser, details

The skin tones have been painted with precise strokes, revealing the finest nuances of colour, for example, in the flushed cheeks or the blue shades in the area of the eyes and the hairline. By contrast, one is struck by the broad brushstrokes and the partly heavy impasto application of colour in the white blouse, the loosely falling green-turquoise dress and the shawl. In the background, the brushstrokes are longer, and have been applied in a dynamic and painterly, sometimes almost a crude, manner. Here, the painting achieves an astounding immediacy, with the red on the left being more thickly applied and the primed canvas still partly visible on the right.

Klimt plays with complementary contrasts and colour resonances in a masterly way. As the defining element of the colour composition, the vivid red of the surroundings is echoed in Fräulein Lieser’s cheeks and sensually accentuated in her lips. The light green of the dress contrasts strikingly with the red tones. Unlike Paul Cézanne, who worked on all the parts of a painting simultaneously in order to achieve balance and tension in its composition, Klimt initially focussed on the subtly nuanced treatment of the skin tones. Fräulein Lieser’s face and hands, outlined in black, are depicted in full detail. Her dress and the shawl with its floral design also display a high degree of completeness. In the floral pattern, the shapes are delineated more lavishly in some places and the open background forms part of the composition of the painting. The surroundings were left still largely undefined at the end of the work’s genesis.

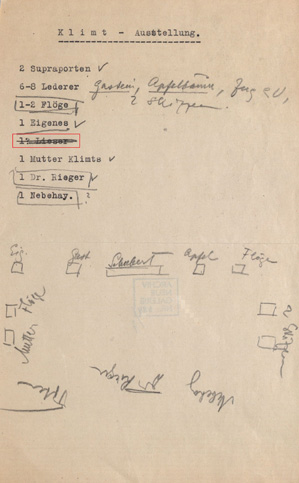

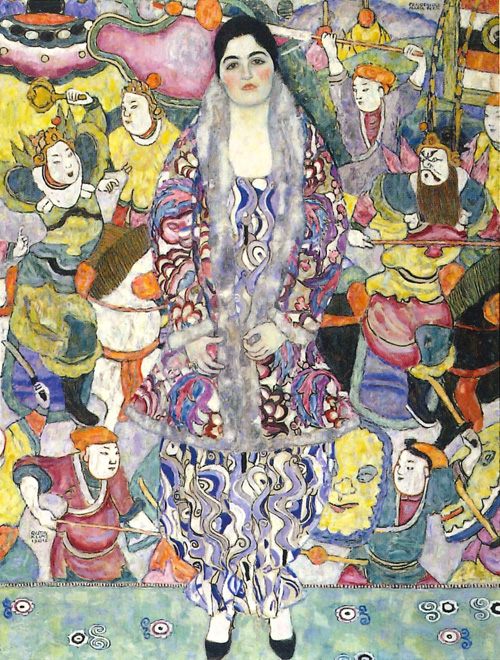

9 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Mäda Primavesi, 1913, detail, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The ornamental motifs drawn in the red background indicate the start of elaborating a decorative design surrounding the figure. But how would Klimt have further developed these graphic outlines in painting? Other portraits of ladies from his late creative years show different design variations. One of the completed paintings is the “Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer”14 (Fig. 20), which is similar to the Lieser portrait in ist front-facing pose and sweeping symmetrical contours. In the upper half of the picture, Asian figures are grouped around Elisabeth Lederer, surrounding her at a fitting distance like an aureole. The “Portrait of Ria Munk III”15, which likewise remained unfinished due to the artist’s death, features a dense, colourful arrangement of flowers. The figure of Ria Munk is enveloped in an aura of flowers, intermingled with tendrils and motifs of a profoundly symbolic nature.16 We are familiar with the exuberantly filled composition, reminiscent of a “horror vacui”, of the “Portrait of Friederike Maria Beer”17 (Fig. 27), which was completed in 1916. Again, in the painting “Lady with a Fan”18 (Fig. 11), we find a scatter pattern of symbols adapted from Asian art, strewn across a background of yellow wallpaper. Klimt’s own Asian artefacts, with which he surrounded himself in his studio in Hietzing, served as a source of inspiration for his repertoire of shapes and motifs.

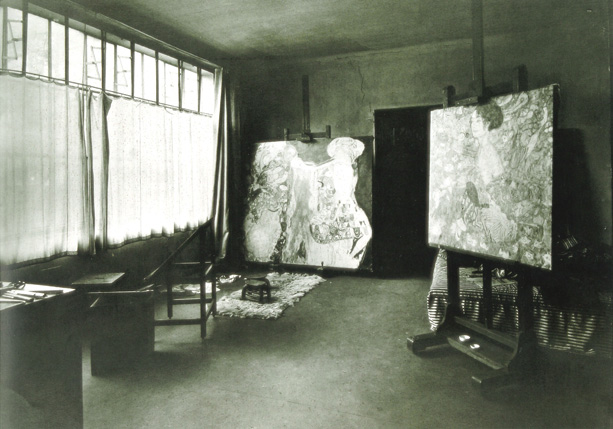

10 Anteroom of Klimt’s studio, Feldmühlgasse 11, 1918

There was also a carpet there designed by Josef Hoffmann, with a diamond motif in its pattern that recurs in a strikingly similar form in the Lieser portrait: Klimt has sketched the diamond with inwardly curved sides as a decorative element in the red background. The scattered linear patterns sketched into the red in the Lieser portrait suggest that Klimt would have enriched the painting with ornamental touches but was by now only missing a few background details. A rather sparse backdrop is imaginable, possibly similar to the one we know from the vibrant pink-purple upper background of the portrait of nine-year-old Mäda Primavesi (Fig. 9), which is enlivened with stylized floral motifs.

11 Gustav Klimt, Lady with a Fan, 1917, private collection

Gustav Klimt was a painter who pursued trailblazing developments and new means of artistic expression. From his Secessionist works at the beginning of Modernism to his icons of the Golden Period and his late work, he always drew on new influences to further develop his unique pictorial language. After abandoning the use of gold in his paintings, it was his encounter with the works of the Fauves and the Post-Impressionists that steered his work in a new direction in which colour took on a pictorial significance. The “Portrait of Fräulein Lieser” vividly illustrates the extent to which he embraced the power of colour and a new painterly freedom in his last paintings. The intensive colouring of the painting and the focus on light, open brushwork reveal Klimt at the height of his late creative period.

12 Klimt’s studio at Feldmühlgasse 11 shortly after the artist’s death, 1918

The painter’s death in February 1918 prevented the completion of the portrait. Klimt himself found it difficult to regard a painting as complete. Thus, he worked on his paintings for years, sometimes exhibiting them in an unfinished state and continuing to make changes to them later. The Lieser painting is one of those late works of Gustav Klimt whose special appeal is also partly due to the “finished or unfinished” question. While large parts of the painting can be regarded as finished, a few details still await their final realisation in paint.

The preliminary sketches in the red background suggest that Klimt would only have made very sparing additions to the picture. Yet is it not precisely the nature of the unfinished that is fascinating from today’s perspective, since it intensifies the painterly openness and expressiveness of this picture? There is no doubt that a work that is in some way “unfinished” particularly appeals to our curiosity, imagination and ability to find associations. What might Klimt have added to the painting next? Would he have offered us still more chromatic refinements? And would it have been possible for any of them to increase the breathtaking beauty of this painting, preserved in its original state?

1 Picture Archive of the Austrian National Library, Negative 113.741.

2 Novotny/Dobai 1967, No. 205, p. 367.

3 Cf. Krug, Gustav Klimt’s Last Notebook, in: Price 2007, pp. 220–221. We should like to thank Dr Hansjörg Krug for making his 2007 typescript “Gustav Klimt’s last notebook” available to us.

4 Strobl 1984, Vol. III, p. 242, Fig. c.

5 Cf. Gaugusch 2016, pp. 1899–1902.

6 Cf. Irene Suchy, “Lilly Lieser – Eine Übersehene, Eine Co-Produzentin der Schönberg’schen Musikgeschichte”, (“Lilly Lieser – An overlooked figure, a co-producer of Schönbergian music history”) in: Österreichische Musikzeitschrift 10, 2008, p. 6–16.

7 Cf. Ernst Ploil’s remarks on “Geschichte und Provenienz” (“History and Provenance”) in this catalogue. Informative are the current research and discoveries of Olga Kronsteiner, published in the newspaper “Der Standard”. Cf. Olga Kronsteiner, Die lange Reise des “Fräulein Lieser”, in: Der Standard, 20.02.2024, p. 19.

8 Alice Strobl identified the sitter as “Margarethe Constance Lieser”, cf. Strobl 1984, Vol. III, p. 112. Weidinger (2007) and Natter (2012) followed Alice Strobl’s identification of the sitter in their catalogues raisonnés.

9 Cf. Olga Kronsteiner, Freie Fahrt für Fräulein Lieser & Co bringen nur Restitutionen, in: Der Standard, 04.02.2024 (https://www.derstandard.at/story/3000000205811/freie-fahrt-f252r-die-klimts, abgerufen 06.03.2024).

10 Strobl 1984, Vol. III, No. 2584–2605, pp. 120–123. We should like to thank Dr Marian Bisanz-Prakken for the valuable information that, in addition to the 22 studies published in Alice Strobl’s catalogue raisonné in connection with the “Portrait of Fräulein Lieser”, she will be including three additional sheets in the supplementary volume on the catalogue raisonné of drawings.

11 Strobl 1984, Vol. III, No. 2603, Fig. p. 123.

12 Strobl 1984, Vol. III, No. 2605, Fig. p. 123.

13 Strobl 1984, Vol. III, No. 2587, Fig. p. 121.

14 Natter 2012, No. 212.

15 Natter 2012, No. 236.

16 On the symbolism of the painting “Ria Munk III” cf. the article by Marian Bisanz- Prakken, “Ria Munk III von Gustav Klimt. Ein posthumes Bildnis neu betrachtet” (“Ria Munk III by Gustav Klimt. A new look at a posthumous portrait”), in: Parnass, issue 3/2009, Sept./Oct., p. 54–59.

17 Natter 2012, No. 145.

18 Natter 2012, No. 237.

Mag. Claudia Mörth-Gasser is an art historian and court-certified expert. She is head of the modern art department at the auction house im Kinsky

History and Provenance

Ernst Ploil

13 Sketchbook 1917, list of income in 1917

14 Gustav Klimt in front of his studio, Feldmühlgasse 11, 1917

According to the authors of the first of the three published catalogues raisonnés of Gustav Klimt’s oeuvre, Dr Johannes Dobai and Dr Fritz Novotny1, 2, 6, then at the beginning of 1917 a member of the family Lieser decided to have his daughter painted by Gustav Klimt. According to their account, Klimt accepted the commission for the portrait in March 1917; in April and May 1917, “Fräulein Lieser” sat — or rather stood — as the artist’s model nine times in his studio. At least 25 studies were made for the oil painting3, which was probably begun in May 1917. On 18th May and 27th June 1917, Klimt received part payments amounting to 5,000 Kronen each from Adolf Lieser (Fig. 13)4, 5. At the time of this commission, Gustav Klimt was engaged in at least ten other painting projects; he was accustomed to working on many works of art simultaneously. On 11th January 1918, he suffered a stroke, as a result of which he died on 6th February. At least eight paintings were still unfinished at the time and were therefore in his studio. Among these unfinished works was the “Portrait of Fräulein Lieser”6.

Gustav Klimt’s estate was handled by a District Court in Vienna that today no longer exists. The court file has not survived, but we know from contemporary sources7 that Klimt did not leave a will and that his estate was therefore divided among his legal heirs — four siblings and the daughter of a predeceased brother. The maintenance claims of his (illegitimate) children and their mothers were settled with one-off payments, and the unfinished paintings were delivered to their respective patrons; the portrait of Fräulein Lieser must therefore have been given to Adolf Lieser1. Of course, all this only applies if one assumes that Adolf Lieser commissioned the painting and that the depicted person was his daughter Margarethe Constance. However, there are also other views regarding this point: see section 3.2.2.

Our painting bears the title “Portrait of Margarethe Constance Lieser” in the catalogues raisonnés of Dr Alfred Weidinger2 and Dr Tobias Natter1. Natter adds a note explaining that “Fräulein Lieser”, as Novotny/Dobai call her in their catalogue raisonné6, had been identified by Alice Strobl as Margarethe Constance Lieser3. According to Natter, Klimt never completed the painting, and after his death it “passed, in an unfinished state, to the commissioning family of the sitter”1.

Alice Strobl based her assumption that the young woman depicted is Margarethe Constance Lieser upon “information kindly provided by Peter-Michael Braunwarth of the Academy of Sciences”. The pictures she refers to, under nos. 2584 to 2605 and no. 3697, as depictions/sketches of Margarethe Constance Lieser all come from Gustav Klimt’s estate and were thus destined to be disposed of differently to the oil painting based on them. There is no evidence in any of them that the person depicted is, specifically, Margarethe Constance Lieser — and not some other member of the Lieser family.

Johannes Dobai’s notes on the catalogue raisonné6 that he authored with Fritz Novotny show that he did not consider the possibility that several persons might come into question regarding the name “Fräulein Lieser”. The authors, Dr Alfred Weidinger2 and Dr Tobias Natter1 , evidently saw it in the same light — however, they were not able to take into consideration some important contemporary indications that have only now emerged:

The “Portrait of Fräulein Lieser” should probably be exhibited at a Klimt retrospective at Otto Nirenstein’s Neue Galerie in Vienna in 1925 (Fig. 16). The photograph depicted in the catalogues raisonnés originates from there as well. The con-temporary caption for this photograph8 reads as follows: Gustav KLIMT. Damenportrait (Frl. Lieser). Gemälde. ANM.: 1925 in Besitz von Frau Lieser, IV., Argentinierstrasse 20. (Fig. 15).

15 Inventory card for the negative „Portrait of Fräulein Lieser“

16 Notes by Otto Kallir-Nirenstein for the Klimt exhibition, Neue Galerie, Vienna 1926

The full name of this “Frau Lieser” was Henriette Amalie Lieser, née Landau. In 1897, she had married Justus Lieser, the brother of the Adolf Lieser mentioned in section 1, divorced him in 1905 and lived in the houses that she owned at Argentinierstrasse 20 and 20a. Three children were born to them: Max, who died shortly after birth, Helene, born in 1898, and Annie, born in 1901. Henriette Lieser descended from the Landau family, and was thus extremely wealthy; she was interested in the arts and moved in artistic circles surrounding Oskar Kokoschka, Alma Mahler, Alban Berg and Gustav Klimt. Following her divorce, her two daughters still continued to live with her for a long time. This leads to the possible conclusion that it might have been Henriette Lieser — and not Adolf Lieser — who commissioned Gustav Klimt to paint a portrait of a girl, that it was also she who made the two part-payments of 5,000 Kronen each that Hansjörg Krug4 “deciphered” from Gustav Klimt’s diary, and that the painting was given to her after Klimt’s death.

In a recently published newspaper article, Olga Kronsteiner9, a specialist in cultural matters, concluded from her examination of an exchange of letters that she had discovered between a (postwar) owner and a museum director called Werner Hofmann that “it was not Silvia Lieser, the widow of Adolf Lieser, but Lilly Lieser who was the owner at that time”.

We have not been able to clarify the precise provenance of the painting following the exhibition at the Neue Galerie in 1925:

Margarethe Lieser emigrated from Austria to Hungary with her mother Silvia Lieser, got married there, emigrated to Great Britain and died there. She could not have taken the painting with her as it can be proven that it was never exported from Austria.

17 Exterior view of Klimt’s studio at Feldmühlgasse 11, 1918

Henriette Lieser remained in Vienna despite the occupation of Austria by Nazi Germany, and continued to live in her house in Argentinierstrasse, but was deported in 1942 and murdered in Auschwitz in 1943. After the end of World War II, her daughters returned to Austria and enforced the restitution of her assets, but our painting was not mentioned anywhere, let alone reclaimed. In the article mentioned in section 3.2.2, Olga Kronsteiner surmises that Henriette Lieser may have exchanged the work of art for food.9

All the catalogues raisonnés indicate that the artwork was “on the art market” at an unspecified point in time. It is quite certain that, since around the mid 1960s, the painting had always hung in the salon of a villa near Vienna, still in the same frame that was probably fitted on the occasion of the Klimt retrospective in 1925. However, there is no clear evidence for a transaction on the art market.

18 Gustav Klimt crossing Tivoli Bridge on his way from Schönbrunn Palace Park to the Café Tivoli, c. 1914

It was these many ambiguities and historical gaps that prompted the current owners to contact the legal successors of the Lieser family and to agree on a “fair and just solution” with them all in 2023, in keeping with the Washington Principles. It has been agreed not to disclose the contents of the said agreement; however, it can be stated that all conceivable claims of all parties involved will be settled and fulfilled through the auctioning of the artwork and on payment of the highest bid. Thus, the agreement essentially means that — from a purely legal point of view — it is immaterial who commissioned the painting from Gustav Klimt and which of the three young ladies in question it portrays.

1 Natter 2012, No. 235, black and white fig. p. 637.

2 Weidinger 2007, No. 245, black and white fig. p. 306.

3 Strobl 1984, p. 111f., black and white fig. p. 114 and Studies no. 2584–2605, p. 120–124. In addition to the 22 studies published in Alice Strobl’s catalogue raisonné, Dr Marian Bisanz-Prakken will include three further drawings in the supplementary volume of the catalogue raisonné.

4 Krug, “Gustav Klimt’s Last Notebook”, in: Renée Price 2007, p. 220f.

5 Conversion rate Kronen to euros (1 Gulden = approx. 2 Kronen; 1 Krone = approx. 6 euros; however, that was before the outbreak of the First World War).

6 Novotny/Dobai 1967, No. 205, p. 367, plate 103, black-and-white fig.

7 Letter from the lawyer Hermann Höfinger, in: Sandra Tretter, Chiffre: Sehnsucht-25, Vienna 2014, p. 18.

8 Picture Archive of the Austrian National Library, No. 113.741.

9 Olga Kronsteiner, “Die lange Reise des Fräulein Lieser” (“The Long Journey of Fräulein Lieser”), Der Standard, 20.02.2024, p. 19.

Dr. Ernst Ploil is a lawyer and specialized in proceedings relating to the “Washington Principles”.

From black and white to colour: On the use of colour in the rediscovered painting “Portrait of Fräulein Lieser” by Gustav Klimt

Franz Smola

Until recently, Gustav Klimt’s painting “Portrait of Fräulein Lieser” was known only from a single photograph, which was moreover only black and white,1 a fate that also befell a whole series of other works by Gustav Klimt that are now considered lost or that no longer exist. This is undoubtedly linked to the turbulent history of many of Klimt’s paintings and also to the often tragic fate of their former owners. In the years between 1938 and 1945, they were frequently subject to persecution, displacement and even murder in the concentration camps of the Nazi regime; their paintings were looted, auctioned or fell victim to the merciless machinery of war.

The colours in the portrait of Fräulein Lieser

The reappearance of a painting that was, for about a hundred years, thought to have been lost is sensational — not least because the chromatic power of the painting has come to light for the first time. Who could have guessed that the unprepossessing dark grey tones of the black and white reproduction could conceal such a glorious shade of orange merging into red in the background, the unusual blue-green, icy hue of the dress and a multitude of pastel colours in the flowery silk shawl! The bold, almost garish, reddish orange of the background is perhaps the biggest surprise.

Given the subject matter of the painting, i.e. the depiction of a rather demure-looking young lady, one might have expected a more delicate colour, such as light green or light blue. In fact, the colour orange is already familiar from other works by Klimt painted around the same time, such as the portrait of Johanna Staude (Fig. 19), which Klimt was still working on in the final weeks before his unexpected stroke.2 In both the Staude and Lieser portraits, the orange background contrasts with blue in the clothing — in Staude’s case a heavily patterned top, and in Lieser’s case the long blue silk shawl draped over her shoulders, displaying a closely woven floral pattern on the back or front, as the case may be. Unlike the portrait of Lieser, however, the portrait of Johanna Staude is not a commissioned work, but rather belongs to that special genre of “fashion portraits”, which Klimt chose to paint relatively frequently, on his own initiative without a commission or fee. The focus here is not on creating a portrait as such, but rather on the artist’s delight in depicting elegant, fashion-conscious ladies, who do indeed always exhibit a special sense of style.

19 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Johanna Staude, 1917-1918, Belvedere, Vienna

20 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer, 1914-1916, private property, New York

In the case of Johanna Staude, this can be seen in her striking blue patterned blouse, which was tailored from an artistic print fabric designed by the Wiener Werkstätte (the “Vienna Workshop”).3 Besides the spectacular reddish orange, the blue of the shawl is another very unusual colour in the Lieser portrait. No similar shade of blue can be found in either Klimt’s late paintings or in the works dating from his earlier periods. Only the background in the portrait of Elisabeth Lederer (Fig. 20), which Klimt worked on from 1914 to 1916, comes close to the blue in the Lieser picture.4

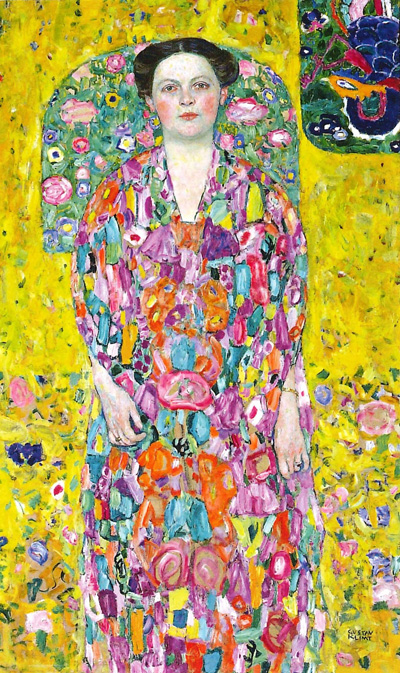

21 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl, 1917–1918, Belvedere, Vienna

The ice-blue background surrounding the daughter of August and Serena Lederer, who is depicted in full length, has a rather greyish hue in comparison to the warmer blue in the Lieser painting, but likewise contrasts with orange in the floor. The two paintings are also comparable in terms of their composition, as both women are portrayed standing and facing to the front. In both cases, the en-face pose is emphasised by a vertically rising floral decoration, which, in the portrait of Elisabeth Lederer, accentuates the outline of the figure as a pyramid-like background motif, and in the Lieser painting is composed of the symmetrically falling, flowery silk shawl mentioned above.

Finally, there is the pale, icy green of Miss Lieser’s dress, a colour that is likewise rarely found in Klimt’s palette. Klimt had intended to use a similar green colour for the background of his unfinished portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl (Fig. 21) — at least, one can conclude this from the glazes with which he initially sketched the background.5

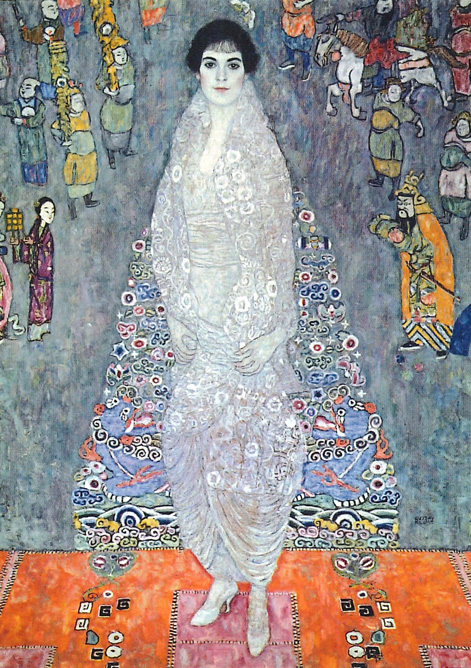

22 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Eugenia (Mäda) Primavesi, 1913–1914, Municipal Museum of Art, Toyota

A comparison of the “Fräulein Lieser” and “Amalie Zuckerkandl” portraits

In dating the portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl, there is some uncertainty as to whether Klimt painted the parts that look finished today, particularly the face, as early as 1913/14, at the time when he presumably also made the numerous studies on paper for this portrait, or whether these parts of the painting first came into being in 1917.

The Zuckerkandl portrait is similar in style to the two portraits of Eugenia Primavesi6 and her daughter Mäda7 (Fig. 22 and Fig. 9) painted in 1913/14. In both Primavesi portraits as well as in the Zuckerkandl portrait, Klimt has endeavoured to give the faces a painstakingly accurate, three-dimensional appearance.

The portrait of Fräulein Lieser shows a comparably precise rendering of the facial features (Fig. 23). These even compare astonishingly closely to those of Amalie Zuckerkandl (Fig. 24). The extremely elegant way in which the finely curved eyebrows of both sitters are drawn, the sensual shape of the lips and — a noteworthy detail— the light reflected in the eye pupils, are surprising and suggest that the two works were probably created very close together in time.

This means that the portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl probably did not acquire its present form until 1917, although Klimt may already have begun the preparatory sketches in 1913/14.

23 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Fräulein Lieser, detail of the face

24 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl, detail of the face, Belvedere Vienna

The question as to the degree of completeness

When looking at the Lieser portrait, a not unimportant question arises: to what extent did Klimt complete the picture? The head, face and hands of the sitter are, indisputably, completely finished and perfectly display Klimt’s artistic mastery. Yet the fact that this painting was not signed by Klimt shows that he himself did not yet consider the portrait finished. Klimt would presumably have further elaborated the background of the picture — one can only speculate as to how. After all, if you look more closely at the orange background of the Lieser painting, one can vaguely discern several shapes outlined in pencil (Fig. 8). These are probably decorative shapes with which Klimt perhaps wanted to enliven the background. Similar shapes outlined in pencil are also to be found under the palegreen, thin layers of paint in the background of the aforementioned portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl. In both cases, we can assume that Klimt intended to add a decorative design to the background at certain points. It is difficult to say what this would have looked like in concrete terms. The numerous preliminary studies in pencil that have survived for both the Zuckerkandl painting and the Lieser portrait unfortunately provide no information in this regard. This is because Klimt generally only finalised the background designs for his portraits at a very late stage, after the sitter had already largely taken shape. There are hardly any surviving preliminary studies for the design of the backgrounds, as Klimt probably mainly developed them directly on the canvas.8 It is possible that the Lieser portrait would have been finished using a sparingly applied scatter pattern.

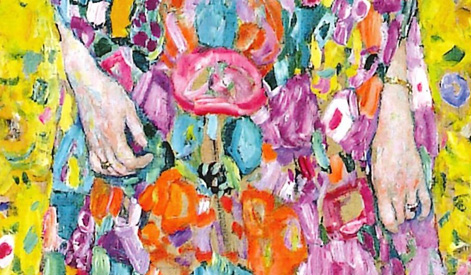

The question is whether Klimt would have elaborated other parts of the picture in greater detail. Here, however, one should exercise great caution in making an assessment, as Klimt always displayed astonishing freedom in his painterly compositions, which hardly permits a final judgement as to what is or is not complete. The scattered pattern of flowers on the long silk shawl in the Lieser portrait (Fig. 25) should, for example, be regarded as completely finished, even if the application of colour may at first glance appear surprisingly dynamic, almost sketchy. However, Klimt always showed considerable creative diversity, particularly in his depiction of decorative elements. For example, one recalls the aforementioned portrait of Eugenia Primavesi (Fig. 26), in which Klimt applies similar, astoundingly free brushwork to render the patterned dress and the background, which is strongly emphasised by means of decorative elements. However, Klimt gave the painting to his clients in precisely this state, and it also bears his signature.9

25 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Fräulein Lieser, detail of the coat

26 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Eugenia (Mäda) Primavesi, detail of the dress

It is certainly difficult to judge whether the depiction of Fräulein Lieser’s pale-green dress is finished or unfinished. Klimt has in fact treated this part very summarily. Perhaps he would later have defined the drapery more precisely and added a piece of jewellery or a border. But even here, caution is called for in making an assessment, as Klimt’s idiosyncratic painting style often intentionally leaves some parts cursorily and almost crudely rendered in order to contrast them all the more effectively with the more detailed areas.

Klimt’s fee for the Portrait of Fräulein Lieser

Fortunately, Klimt’s own notes provide a good record of his work on the painting and the payments he received for it. Klimt had invited Miss Lieser to a total of nine sittings, which took place at his studio in Hietzing in April and May 1917. In May and June 1917, he received a payment on account of 5,000 Kronen (Fig. 13).10 In comparison, Klimt had received two payments of 2,000 Kronen each for the portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl in November and December 1917.11 The reason for the much lower fee for the Zuckerkandl painting is probably that large sections of the picture were still unfinished. Conversely, in view of the much higher fee for the Lieser painting, we can conclude that Klimt and the commissioning family probably considered it to be largely complete.

27 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Friederike Maria Beer, 1916, Museum of Art, Mizne Blumenthal Collection, Tel Aviv

This sum of 10,000 Kronen as part payment was a very normal price for customers to have paid a few years earlier for a finished portrait by Klimt. Karl Wittgenstein, for example, had paid precisely that amount fo the portrait of his then 23-year-old daughter Margaret, completed in 1905.12 However, due to the spiralling inflation caused by the war, prices increased in the following years.

For example, Hans Böhler had to pay 20,000 Kronen for the portrait of his girlfriend Friederike Beer-Monti, completed in 1916 (Fig. 27) — an astronomical sum at that time, notwithstanding all the price increases due to inflation. As Hans Böhler recalled, one could have bought a villa on Lake Geneva for that amount.13 This might seem to be a slight exaggeration, but at the turn of the century it was actually possible to buy a villa in the Salzkammergut region, complete with furnishings, for 40,000 Kronen — around four times the value of a Klimt portrait.14

Klimt could presumably have expected a further payment, possibly an additional 5,000 Kronen, when the finished Lieser painting was delivered; the final price would then have been 15,000 Kronen, which would have placed the painting in a very ambitious price range, even by Klimt’s standards.

Klimt’s clients and their expectations

Thus, even during his lifetime, Klimt’s portraits already commanded prices that can only be compared with property values. Consequently, his clients could only have been extremely wealthy individuals.

Particularly where there was no close personal relationship with the master, the clients’ expectations were certainly strongly shaped by social norms. Their main concern was to ensure the most representational depiction possible of the persons portrayed in the pictures, in keeping with their social status. By emphasising a certain demure reserve in the young lady in the portrait of Fräulein Lieser, giving her a somewhat shy gaze, an expression that is further emphasised by the slightly flushed cheeks so typical of Klimt, he confirms and reinforces the ideal of the “young maiden” that was of paramount importance for young ladies from the best families at that time.

28 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Gertrud Loew, 1902, Lewis Collection, London

For Klimt, a unique and legendary admirer and proponent of feminine beauty, probably no motif lay closer to his heart than such representational portrayals of pretty young ladies. Over the course of many creative years, it was in this very artistic field that he had achieved his greatest works. The portrait of Gertrud Loew (Fig. 28), which Klimt painted in 1902, can serve as an example from earlier years.15

29 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Fräulein Lieser, detail

In the sensual charm of the then 19-year-old Gertrud Loew, her likewise shy gaze and a posture that again expresses a certain demureness, Klimt presents us with the epitome of a sheltered young lady who was, incidentally, to marry shortly afterwards. In the portrait of Fräulein Lieser, too, Klimt adheres to this “young maiden” ideal, unperturbed by the political, social and economic developments that people in Vienna and Austria-Hungary were facing fifteen years later. As in all the paintings that Klimt created in his later years, the drama of real life is completely absent from the Lieser portrait, which is filled with beauty and harmony. Only the colours of the paintings and their intensity have changed over the years. Whereas Klimt’s 1902 painting of Gertrud Loew’s dress was a symphony in white much admired by her contemporaries, Klimt’s 1917 painting of Fräulein Lieser presents a polyphonic, melodious symphony of spring and summer colours.

1 Until now, the only reproduction was found in Novotny/Dobai 1967, no. 205, p. 367, where (p. 422) reference is made to the Picture Archive of the Austrian National Library.

2 Natter 2012, No. 240.

3 Franz Smola, “Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Johanna Staude (1917–1918): New Insights into the Subject and her Portrait´s Creation”, Belvedere Research Journal 1 (2023), https://doi.org/10.48636/brj.2023.1.101339.

4 Natter, 2012, No. 212.

5 Natter, 2012, No. 241.

6 Natter, 2012, No. 207.

7 Natter, 2012, No. 202.

8 “Letzte Schaffensjahre” (“The final creative years”), in: Gustav Klimt-Database / Klimt-Foundation, Vienna: https://www.klimt-database.com/de/klimtwerk/ 1914-1918/maler-der-frauen. Accessed on 14.05.2023.

9 It was possible to admire this picture at the Vienna exhibition “Klimt Inspired by Van Gogh, Rodin, Matisse”, Belvedere, Vienna, 3rd February – 29th May 2023.

10 See the article by Claudia Mörth-Gasser in this catalogue.

11 Strobl 1984, Vol. 3, p. 242.

12 Natter 2012, No. 169.

13 Martin Suppan, Hans Böhler: Leben und Werke (“Life and Works”), Vienna: Edition M. Suppan, 1990, p. 36, cited in: Janis Staggs, Kommentar zum Gemälde Gustav Klimt, “Friederike Maria Beer” (“Notes on the painting ‘Friederike Maria Beer’”), in: “Modern Art at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art”, Museum of Art, Tel Aviv, opening planned for autumn 2024. My sincere thanks to Janis Staggs of the Neue Galerie New York, for sending me an advance copy of the manuscript.

14 “Zitate und Bilder” (“Quotes and pictures”), bearbeitet von Franz Smola, in: Tobias G. Natter, Franz Smola, Peter Weinhäupl (ed.), Klimt persönlich. Bilder – Briefe – Einblicke (“Klimt’s personal life. Pictures – letters – insights”) (exhibition catalogue Leopold Museum, Vienna, 24th February – 27th August 2012), Vienna 2012, p. 285.

15 Natter 2012, No. 145.

Dr. Franz Smola is curator of the late 19th & early 20th century collection at the “Österreichische Galerie Belvedere” in Vienna.

Less is More

Rainer Metzger

“I can paint and draw,” Gustav Klimt once wrote in a note that has been preserved at the Vienna City Library. “I believe that, and some people say they believe it too. But I’m not sure whether it’s true. Only two things are certain: 1. There is no self-portrait of me. I am not interested in my own person as the ‘subject of a picture’, but rather in other people — above all, women — and even more so in other visual manifestations. I’m convinced that I’m not particularly interesting as a person… 2. I don’t feel comfortable expressing myself in spoken or written words, particularly when I’m expected to make statements about myself or my work… Anyone who wants to know something about me — as the artist, who alone is worthy of attention — should look carefully at my pictures and try to discern from them what I am and what I want.”1

30 Gustav Klimt in his painter’s smock, 1902, photographed in the centre hall of the Vienna Secession before the opening of the XIV. exhibition, the so-called Beethoven exhibition

Klimt sees himself as being “not particularly interesting as a person”. He characteristically rejects any VIP status, and what he is saying here can be summed up as follows: the artist’s ego is less important than the self of the oeuvre. It is not the grand ego of a creative figure that asserts itself with heart and soul in his work; rather, that work has a life of its own. Perhaps it is a generational phenomenon: Klimt remains a proponent of the 19th century, with its ideals of autonomy and ist art cults. In the artificial world he creates, the motifs literally revolve around themselves — centred upon themselves. And the people he depicts are likewise preoccupied with themselves: with their eroticism; with their age; with their appearance and their outfits; with the sensations and sensibilities of their bodies. As Klimt so eloquently puts it, there isn’t much to say: it’s enough to show.

31 Group portrait of members of the Vienna Secession on the occasion of the XIV. exhibition, 1902. Back row from left to right: Anton Nowak, Gustav Klimt, Adolf Böhm, Wilhelm List, Maximilian Kurzweil, Leopold Stolba, Rudolf Bacher; Front row from left to right: Kolo Moser, Maximilian Lenz, Ernst Stöhr, Emil Orlik, Carl Moll.

Klimt makes one of the most enchanting gestures in his oeuvre in the shape of the portrait that has just come to light, showing a young lady about whom we know only that her surname is Lieser. Reductiveness is not necessarily a quality of this master: quite the reverse — at times, his pictures overflow with sophistication and showy embellishment. An extravagant stylisation remains the hallmark of his work to this day, and the word “golden”, which describes both a material and an overall impression, sums it up very well. Klimt was in tune with the taste of a public that could be as little sure of its aesthetic standards as it was of its social status. It was all a little precarious, and the cocoons of costly finery in which he wrapped his luxurious creations as if it was natural to them place his sitters — who are “above all, women” — in the psychosocial milieu of the inner circle.

32 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Fräulein Lieser, detail

33 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II, 1912, detail, private property

But then, an unforeseen openness moved into the ivory tower. Perhaps Klimt took the trip to Spain and France in autumn 1909 because he wanted to change his style or perhaps the trip, on which he was accompanied by his colleague and fellow Secessionist Carl Moll, helped to refresh his routine. “The squares are over,” the two wrote to Josef Hoffmann, the grand master and champion of the dominance of décor in Vienna, who had stayed at home. It was not just the square schematism of the Secession style that was over: it was also the end of the exuberant penchant for the Gesamtkunstwerk — i.e. the “total work of art”, a synthesis of the arts — that united them. Klimt said goodbye to everything that did not belong to the orthodoxy of painting and drawing. No gold, no sequins, no “standard-issue” pictures. A painting is paint on canvas, and this was now made plainly recognisable. His public, perhaps glad of this gentle call to order, followed suit. It appears that the amount of money and patience they were prepared to invest for a painting from his hand even increased.

34 Gustav Klimt in 1917 at the age of 55

It’s a big word — the key to the master narrative of the 20th century: Modernism. And it can be said that Klimt joined the phalanx of innovators whose world-shaking wisdom consisted in acknowledging that painting is a mixture of colours on a flat surface. Perhaps it was Henri Matisse who had recognised this fact most conclusively up to that point and who now showed Klimt the way in Paris. And perhaps, in that very city, Edouard Manet, the founding figure of Modernism, provided help and support from the past.

For when we regard the face of Fräulein Lieser, with Klimt’s masterful harmonisation of its features and precise recording of what, quite simply, constitutes a face — this close examination of the facial features is reminiscent of the way that Manet captured his favourite model, Victorine Meurent, on canvas.

In his later years, Klimt became a genuine Modernist, a proponent of “less is more”, a pioneer of the contemporary. And this is precisely where he remained rooted in the 19th century: he only found his very own “être de son temps”, his own way of being in step with the times, in his later years. Had he belonged fully to the new era, it would have manifested in his early work. Instead, that was left to a Schiele or a Kokoschka. Klimt is no avant-gardist: he thereby shows himself all the more clearly to be a Modernist.

1 Otto Breicha (ed.), Klimt – Die Goldene Pforte. Bilder und Schriften zu Leben und Werk (“Klimt – The Golden Gate. Pictures and writings relating to his life and work”), Salzburg 1978, p. 33.

Prof. Dr. Rainer Metzger is an art historian, curator and critic. He has taught at the State Academy of Fine Arts in Karlsruhe since 2004, and is the author of numerous publications on art history, including the book “Gustav Klimt. Drawings & Watercolours”, published by Brandstätter Verlag in 2005.

Gustav Klimt

-

1862

Gustav Klimt is born on 14th July in Baumgarten near Vienna, as the son of the engraver Ernst (1834–1892) and his wife Anna Klimt (1836–1915, née Finster).

-

1876–1883

Gustav Klimt and his brother Ernst (1864–1892) are admitted to the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts at the Imperial Royal Austrian Museum of Art and Industry, where they study until 1883. There, the brothers get to know Franz Matsch (1861–1942).

-

1883–1891

The Klimt brothers and Franz Matsch found the “Künstlercompagnie”, an artists’ association. The collective moves into its own studio and receives important commissions for interior design until 1892: it creates the décor for the theatres in Fiume (Rijeka), Karlovy Vary and Bucharest, as well as the ceiling design for the Hermes Villa in Lainz. This is followed by commissions for the frescoes in the stairwells of the newly built Burgtheater and in the Kunsthistorisches Museum (Museum of Fine Arts) in Vienna.

-

1892

Death of his father and brother Ernst Klimt in July. Klimt assumes the guardianship of his niece Helene. The Künstlercompagnie is disbanded.

-

1894

Commission for the faculty paintings for the main auditorium of the University of Vienna. Klimt designs the pictures for “Philosophy”, “Medicine”, “Jurisprudence” and the spandrel pictures, Matsch designs the pictures for “Theology”. After years of controversy, Klimt will reject the commission in 1905.

-

1897

Klimt and a number of other artists leave the Künstlerhaus. Klimt is a founding member of the Vienna Secession and becomes its first president.

-

1898

The portrait “Sonja Knips” marks the beginning of Klimt’s rise to become a sought-after portrait painter of high Viennese society. He paints his first landscapes during his summer holiday with the Flöge family in the Salzkammergut region.

-

1902

Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze is presented to mark the 14th exhibition of the Vienna Secession. Klimt paints a portrait of the nineteen-year-old Gertrud Loew.

-

1903

Klimt goes on trips to Italy, Ravenna and Rome, where he finds artistic inspiration for the “Golden Period”. Big Klimt collective exhibition at the Secession with over 80 works. Founding of the Wiener Werkstätte (“Vienna Workshop”).

-

1904

Josef Hoffmann is commissioned by the Belgian industrialist Adolphe Stoclet to build a palace in Brussels. Klimt designs the marble frieze in the dining room.

-

1905

The Klimt Group, including Carl Moll and Josef Hoffmann, leaves the Secession.

-

1907

Klimt paints the portrait “Adele Bloch-Bauer I”.

-

1908–1910

The Klimt Group holds the “Kunstschau” exhibition on the site of today’s Konzerthaus in Vienna. There, Klimt displays his painting “The Kiss”, which is acquired by the Ministry of Education for the Moderne Galerie in the Belvedere. The trip to Paris in 1909 provides important artistic inspiration and heralds the end of the “Golden Period”. In 1910, Klimt takes part in the 9th Venice Biennale.

-

1911

Klimt moves into his last studio, at Feldmühlgasse 11 in Vienna’s 13th district. His painting “Death and Life” is awarded the first prize at the International Art Exhibition in Rome.

-

1912–1916

Colourful portraits of women are executed, including “Adele Bloch- Bauer II”, “Mäda Primavesi”, “Eugenia (Mäda) Primavesi”, “Elisabeth Lederer” and “Friederike Maria Beer”. Klimt has exhibitions in Budapest, Munich, Mannheim, Prague and Rome. In the summer of 1916, he traveled to Lake Attersee for the last time with Emilie Flöge.

-

1917

Klimt works on multiple paintings at the same time, none of which he completes: “Die Braut”, “Adam und Eva”, the “Dame mit Fächer”, “Der Iltispelz”, the portraits “Amalie Zuckerkandl”, “Johanna Staude”, “Ria Munk III”, “Damenbildnis in Weiß”, “Damenbildnis en face” and the “Bildnis Fräulein Lieser”.

-

1918

Klimt dies on 6th February due to a stroke. He leaves the unfinished paintings unsigned in his studio.

Sources of figures

Fig.

1 Photo Pauline Hamilton, private property

2 ÖNB Picture Archives, negative no. 113.741

3 © Auction house im Kinsky GmbH, Vienna

4 Wiener Illustrierte Zeitung, vol. 29, issue 40, 4 July 1920, p. 574; Annie Lieser: photo Madame d’Ora, illustrated in: Moderne Welt, vol. 4, issue 8, January 1923, p. 6

5 Inv. no. LM 1340 © Leopold Museum, Vienna

6 Tobias G. Natter (ed.), Klimt and the women of Vienna’s Golden Age: 1900–1918., (exhibition catalogue Neue Galerie, New York, 22 September 2016–15 January 2017), Munich, London, New York 2016, colour ill., p. 179

7 © Auction house im Kinsky GmbH, Vienna

8 © Auction house im Kinsky GmbH, Vienna

9 © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

10 Photo Moriz Nähr

11 Photo: Archivart / Alamy Stock Photo, illustrated in: Tobias G. Natter, Gustav Klimt: Interiors, Munich/London/New York 2023, plate 38, p. 181

12 Photo Moriz Nähr

13 Strobl 1984, vol. III, p. 242, fig. c.

14 Photo Moriz Nähr, Neue Galerie New York

15 ÖNB Picture Archives Vienna, no. 113.741

16 © Belvedere, Vienna

17 Photo Moriz Nähr, ÖNB Vienna © ÖNB Vienna, inv. no. 94882 E.

18 © ÖNB Vienna, inv. no. PF 31931 C(3)

19 Inv. no. 5551 © Belvedere, Vienna

20 © Verlag Galerie Welz, Salzburg.

21 Inv. no. 7700 © Belvedere, Vienna.

22 © Municipal Museum of Art, Toyota.

23 © Auction house im Kinsky GmbH, Vienna

24 Inv. no. 7700 © Belvedere, Vienna.

25 © Auction house im Kinsky GmbH, Vienna

26 © Municipal Museum of Art, Toyota.

27 Natter 2012, p. 629

28 © Verlag Galerie Welz, Salzburg.

29 © Auction house im Kinsky GmbH, Vienna

30 Photo Moriz Nähr, ÖNB Vienna © ÖNB Vienna, inv. no. Pf 31931 D (3a)

31 Photo Moriz Nähr, ÖNB Vienna © ÖNB Vienna, inv. no. 94924 D

32 © Auction house im Kinsky GmbH, Vienna

33 Natter 2012, p. 618

34 Photo Moriz Nähr

35 Photo Moriz Nähr

35 Gustav Klimt with a cat in the garden of his studio at Josefstädter Straße 21, 1912