0750

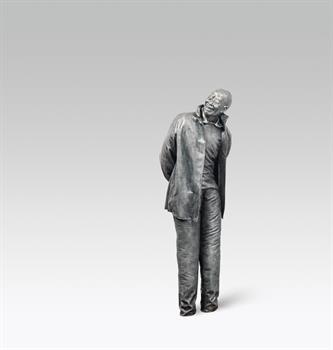

Juan Muñoz*

(Madrid 1953 - 2001 Ibiza)

„Chino mirándose en espejo redondo“

polyester resin, mirror

figure: 142 x 48 x 43 cm

mirror: 90 cm diameter

Unique

Provenance

acquired in 1999 directly from Juan Muñoz (during Art Basel);

since then private collection, Brasil

Estimate: € 300.000 - 500.000

Auction is closed.

The „Chinese looking at himself in a round mirror” is smiling happily – a perfectly mundane sight. But something is not quite right here: is it the small build of the man? Is it his feet, hidden under the overlong pants? Or is it just his smile, frozen into a grimace?

And so we have delved right into the fascinating world of Juan Munoz. The Spanish artist has created the figure in 1999, and it belongs to the series of sculptures with Asiatic features which constitute a milestone in his oeuvre. For the first time, the so-called “Chinese” appear in 1996 in the work “Plaza (Madrid)”, which is an installation comprising five figures standing in a space and apparently conversing. He executed this work for the Museum Palacio Velazquez in Madrid, today it is part of the collection of the National Museum Reina Sofia, also in Madrid.

All their faces are alike. Munoz used the same model - an Art Nouveau bust - for all of his Chinese figures. Also, at the same time, their faces recall Franz Xaver Messerschmidt’s character heads from the 18th century. “I try to make the work engaging for the spectator. And then unconsciously, but more interestingly, I try to make you aware that something is really wrong. When I started making the smiling Chinese statues, I had two assistants who told me that they didn’t like to be left alone at night in the studio with all these figures.” (Neal Benezra und Olga M. Viso in Juan Munoz ©University of Chicago Press 2001, pages 145-150)

While the Chinese’ broad smile might at first arouse amusement, it does irritate the spectator too. He has just to look in the mirror to understand that the statue could very well be laughing about him. The viewer might stand close to the figure, but emotionally he is far removed from it: Munoz is a master at building up tension between proximity and distance. The spectator has to accept that his presence is of no importance to the significance of the sculpture. Therefore, the artist’s reflection: “I believe that the best work can exist without a spectator” (B.J. Scheuermann in Juan Munoz – Rooms of My Mind, Ausstellungskatalog, K21 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, 2006, page 158.) comes as no surprise.

The onlooker is just a foreigner, an intruder into the Chinese’s world; both are incapable of any exchange. The impossibility of communication is a recurrent motive in Munoz’ work, and this statue is almost prescient. It points to our present, in which the use of smartphones is changing our communication beyond recognition. The same can be said for the artist’s fascination with narcissism. We come upon the statue in a moment of self-contemplation, which makes us uncomfortable. Because – Do we want to be seen while looking at someone else? Or at ourselves, even?

Munoz, born in 1953, became known to a wider public in the 1980-ies with sculptural installations in which he put humanized figures in constructed spaces. Human? His representations always have something that is quite off – before the Chinese, he created strange dwarfs, ventriloquists or cone-shaped figures. All of them tell a story, though: “I remember being called a storyteller in the early 1990-ies, and therefore accused of not really being an artist. But there’s nothing wrong with being a storyteller.” (Neal Benezra und Olga M. Viso in Juan Munoz ©University of Chicago Press 2001, pages 145-150)

Munoz was awarded the Spanish National Arts Award and was the first Spanish artist from whom the Tate Modern Gallery in London commissioned a large work for their turbine hall. “Double Bind” from 2001 was one of the last works the artist completed before his sudden death at the age 48 that same year. His works are included – among others – in the collections of Tate Modern, MOMA New York or Hirshhorn Museum Washington. (Alexandra Markl)